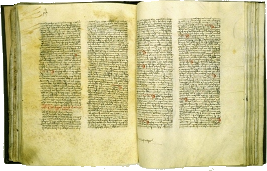

MIDDLE AGES: EARLY REFORMS TOWARDS STANDARDIZATION

Although the feudal and stately structure of the time promoted the existence of a great diversity of measurement units, the determination of weights and measures was a royal privilege and, from an early age, there were attempts to standardize weights and measures.

In 1179, the charters given by King Afonso Henriques to Coimbra, Santarém and Lisbon mention an alqueire (bushel) much larger than the old one, which would be about 40% smaller than the new alqueire. Several later documents refer to the existence of the small measure and the large measure, or large rasa.

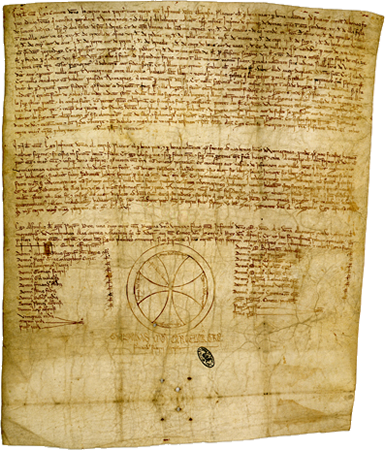

In 1352, in the Cortes (Courts) of Lisbon, the people’s representatives asked the king to standardize the various measures, for length, volume and weight. One of the situations concerned the measures used for coloured cloth, as the buyers bought according to “large” measures and sold using smaller measures, causing losses to their customers. In this particular, King Afonso IV agreed, ordering that everyone should use the alna (i.e., the côvado) of Lisbon.

As for the measures for volume (for flour, wine and olive oil) and weight, the king understood that he would have to assess the situation better, as any decision would also affect other municipalities that were not represented in these Cortes. Meanwhile, the king died without making any decisions on the measurement systems.

The greatest reform of volume measures in the first dynasty occurs with King Pedro I, who slightly increased the volume of the alqueire, maintaining a direct relationship between the measures used for liquids and solids: one almude had the capacity of two bushels, worth each bushel 6 canadas.

The old alqueire was 8/9 of the “King Pedro’s alqueire”. The system kept a previously known structure: the moio was divided into 4 quarteiros, 16 teigas, 32 almudes and 64 alqueires, which meant that one almude was still worth 2 alqueires and 12 canadas (1 alqueire was worth 6 canadas). Gradually, other former units of volume, such as the sesteiro, the puçal and the quarta, fell into disuse.

In the Courts of Elvas, in 1361, the king decreed that the measures of wine should be assessed by the almude of Lisbon.

Regarding weight, in those same Courts it was determined that those used to weigh some products (eg. meat, wool and linen) should be made of iron and not stone, and marked and checked by the arroba of Lisbon.

As to weighing meat, the king decreed that the arráteis folforinhos could still be used as units of weight where this was the custom, checking the corresponding weights against the standard of Santarém. It was therefore concluded that Lisbon had the standard of the arroba and Santarém kept the standard of the arrátel folforinho, which was worth 3/4 of the arrátel mourisco (Moorish arratel).

In accordance with the Law of Almotaçaria of 1253, the arrátel would be 12.5 ounces, but in the 14th century, we found the “legal” arrátel weighing 14 ounces. However, it is uncertain whether this change is related to the reforms of King Pedro I.

However, despite these attempts at uniformity, various types of marks, such as those of Cologne, of Tria (Troys) and of marçaria (grocer) continued to be used, as well as several types of arráteis.

The obligation to use iron weights (arrobas) and not stone was reinforced during the reign of King João I, in the Courts of Coimbra (1391).

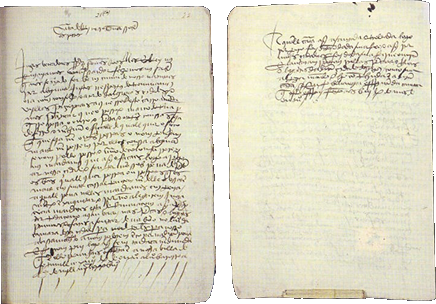

In the courts that started in Elvas in 1481 and ended in Viana in 1482, during the reign of King João II, it was determined, at the request of the peoples, that all measures should be of the same capacity.

In 1487 King João II found that “the primary cause of the deviation of those weights comes from the existence of two types of ounces, the ounce of the mark of the Colonha (Cologne) which was ordered to be used for weighing gold and silver, and the ounce of the mark of marçaria (grocer) which was ordered to be used for general merchandise”. Thus, in that same year, King João II asked the Lisbon City Council and the representatives of the guilds to give their opinions about the idea of using a single type of mark for all of the products (“either the mark of Cologne or the marçaria mark”) and a new system of weights according to the following structure:

- onça (ounce) = 6 grãos (grains);

- marco (mark) = 8 ounces;

- arrátel = 2 marks = 16 ounces;

- arroba = 32 arráteis;

- quintal = 4 arrobas.

In the following year, D. João II ordered that people should no longer use the mark of Tria (Troyes), but instead, they should use the mark of Cologne: “that the weight and mark of Tria used for weighing gold and silver and other things, made of iron, shall not be held or used by any officer or any other person, for weighting any products, but, instead, they must use the weight and mark of Cologne, thus we order… “.

In the Courts of 1490, following the request of some municipalities, King João II accepted that part of the country used the measures of Porto and not those of Santarém.

King João II died in 1495 without having applied the reform of the weight system based on the 16 ounce arrátel that he had proposed.